Student blog: a closer look at the right to repair

Hey! My name is Jaylani and I’m in my first year at TEDI-London. Earlier this year we kicked off a term 2 Prototyping module with a talk and discussion about the impact of the multifaceted Right to Repair campaign. Facilitated by Danielle Purkiss from the Big Repair Project, the discussion really highlighted to me the importance of telling stories about the longstanding culture of fixing – a culture vital but often overlooked.

In this blog I’d like to share my own experiences and observations on the complexities of repair, inspired by the ambitious community leaders I’ve met at my local repair cafés.

Do people really want the right to repair?

I was introduced to the idea of the Right to Repair in secondary school. At this time, a lot of us received a hand-me-down phone from a sibling or family member. Sometimes the phone or tablet needed a new screen or a battery swap and we wouldn’t always go to the manufacturer to get this done. For me and my peers, DIY repairs were normal and sometimes encouraged.

However, with the amount of technology embedded in our day to day lives, it can be hard to keep up with the art of repair. Moore’s Law is the observation that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit (IC) doubles about every two years. This helps to put into perspective how fast technological developments in consumer products occur. As a result, I feel we have become more comfortable with less control over our devices from manufacturers, and consequently become less curious in how to go about repairing them.

The Right to Repair campaign has worked to raise awareness on both a national and regional scale, with increasing support from the Consumer Protection Committee of the EU Parliament. This campaign has seen legislative success, but as this article from Advanced Science News concludes, “It’s important to acknowledge that this progress is not inevitable, as there are numerous stakeholders pushing back against these efforts…”

This leads me to question, do people really want the right to repair? I’m not convinced the average person genuinely desires the freedom to repair. But with a rise in advances in the tech industry, there comes an increased responsibility for individuals to remain well-informed. For me, the battle for the right to repair is about fostering an environment where careers and industries adapt to the rapid pace of change, beginning with granting individuals access to necessary resources and knowledge. This is where I’ve seen the power of repair cafés come in.

Empowering repair in the community

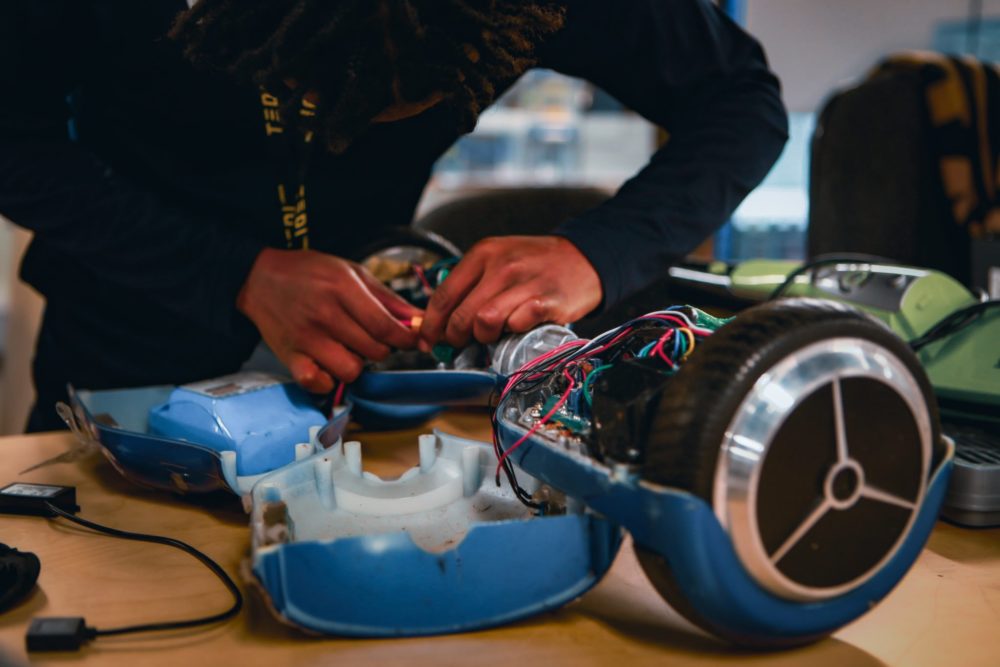

I started taking part in local repair cafés last year and have supported setting up TEDI-London’s very own student-led repair club. It’s a space to help members of the community with repairs, share handy tips to support their own future fixing, and consequently make a positive impact in reducing e-waste.

The experience has also reminded me that the culture of repair shouldn’t just be limited to personal gadgets either. Parallels can also be drawn between tech and fashion. When I was searching for spaces for electronic repair, I often found hubs dedicated to textile repairs.

At its core the Right to Repair campaign is challenging the consumer culture that values disposability over sustainability. In recent years the UK was regarded as the 2nd largest contributor to e-waste after Norway; this means roughly 23kg of electronic waste per person.

It also shines a light on the disproportionate extraction methods taken to manufacture these devices. Kyle Wiens, the founder of the online repair community IFixit, highlights the damaging effect caused by the unmonitored and unsustainable use of certain materials still being a sad reality: “The environmental impact of manufacturing the things that we have is significant. The phone that’s in your pocket for example, which weighs like 8 ounces, took over 250 pounds of raw material dug out of the ground to make.”

The environmental impact of e-waste is a significant global challenge that manufacturers, consumers and us as future engineers must continue to tackle alongside the right to repair. From speaking with volunteers at the TEDI-London repair club and members of other community hubs, we know there is a long way to go, but there is a general vote of confidence that as consumers gain more control of the laws that limit their ability to fix their devices, people will be able to embrace the freedom to repair.

Read more about benefits of repair.

More Student blogs articles

A day in the life of a TEDI-London student: George